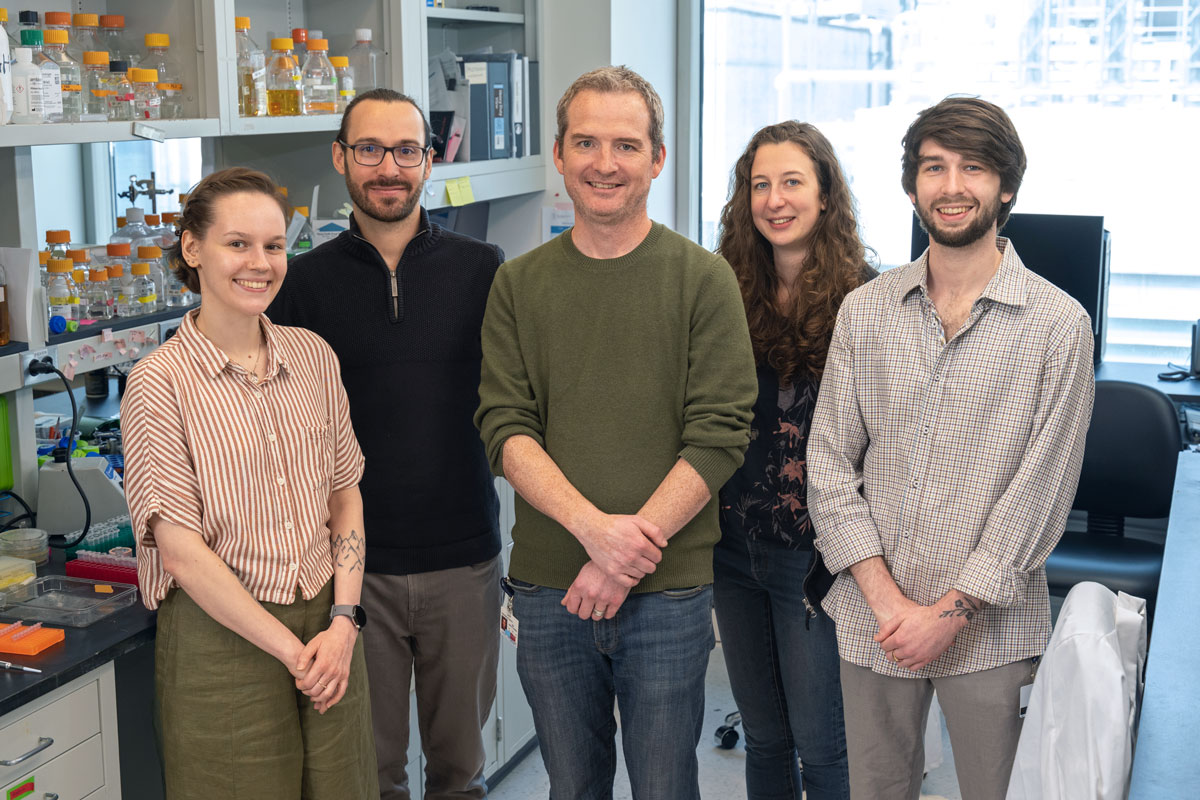

The Iestyn Whitehouse Lab

Research

The Whitehouse lab is broadly interested in understanding how chromatin functions in the regulation of cellular processes such as DNA replication, gene transcription and epigenetics. We focus on understanding basic mechanisms and use a combination of biochemical, molecular biological and genomics approaches. We like to develop new technology and are particularly interested in the development and application of single molecule technologies such as Nanopore sequencing and single molecule indexing strategies.

Research Projects

Featured News

Publications Highlights

Balancing act of a leading strand DNA polymerase-specific domain and its exonuclease domain promotes genome-wide sister replication fork symmetry. Meng X, Claussin C, Regan-Mochrie G, Whitehouse I, Zhao X.Genes Dev. 2023 Jan 26. doi: 10.1101/gad.350054.122.PMID: 36702483

Single-molecule mapping of replisome progression. Claussin C, Vazquez J, Whitehouse I.Mol Cell. 2022 Apr 7;82(7):1372-1382.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.02.010. Epub 2022 Mar 2.PMID: 35240057

DNA replication through a chromatin environment. Bellush JM, Whitehouse I.Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017 Oct 5;372(1731):20160287. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0287.PMID: 28847824

DNA-mediated association of two histone-bound complexes of yeast Chromatin Assembly Factor-1 (CAF-1) drives tetrasome assembly in the wake of DNAreplication. Mattiroli F, Gu Y, Yadav T, Balsbaugh JL, Harris MR, Findlay ES, Liu Y, Radebaugh CA, Stargell LA, Ahn NG, Whitehouse I, Luger K.Elife. 2017 Mar 18;6:e22799. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22799.PMID: 28315523

Spatiotemporal coupling and decoupling of gene transcription with DNAreplication origins during embryogenesis in C. elegans. Pourkarimi E, Bellush JM, Whitehouse I.Elife. 2016 Dec 23;5:e21728. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21728.PMID: 28009254

People

Iestyn Whitehouse, PhD

Director of the Center for Epigenetics Research (CER)

- Molecular biologist Iestyn Whitehouse investigates chromatin structure and the function of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling enzymes.

- PhD, The University of Dundee

- [email protected]

- Email Address

- 212-639-8398

- Office Phone

Members

Open Positions

To learn more about available postdoctoral opportunities, please visit our Career Center

To learn more about compensation and benefits for postdoctoral researchers at MSK, please visit Resources for Postdocs

Get in Touch

-

Lab Head Email

-

Office Phone

Disclosures

Members of the MSK Community often work with pharmaceutical, device, biotechnology, and life sciences companies, and other organizations outside of MSK, to find safe and effective cancer treatments, to improve patient care, and to educate the health care community. These activities outside of MSK further our mission, provide productive collaborations, and promote the practical application of scientific discoveries.

MSK requires doctors, faculty members, and leaders to report (“disclose”) the relationships and financial interests they have with external entities. As a commitment to transparency with our community, we make that information available to the public. Not all disclosed interests and relationships present conflicts of interest. MSK reviews all disclosed interests and relationships to assess whether a conflict of interest exists and whether formal COI management is needed.

Iestyn Whitehouse discloses the following relationships and financial interests:

No disclosures meeting criteria for time period

The information published here is a complement to other publicly reported data and is for a specific annual disclosure period. There may be differences between information on this and other public sites as a result of different reporting periods and/or the various ways relationships and financial interests are categorized by organizations that publish such data.

This page and data include information for a specific MSK annual disclosure period (January 1, 2024 through disclosure submission in spring 2025). This data reflects interests that may or may not still exist. This data is updated annually.

Learn more about MSK’s COI policies here. For questions regarding MSK’s COI-related policies and procedures, email MSK’s Compliance Office at [email protected].