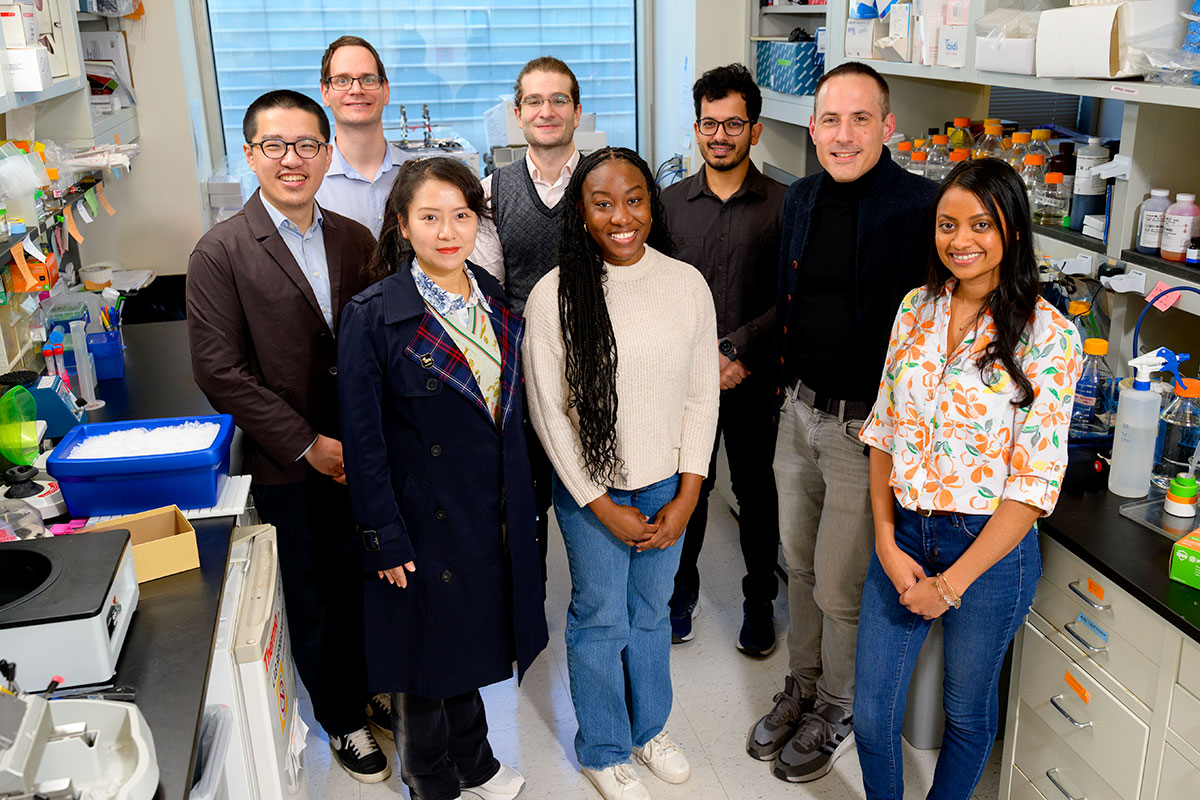

The Philipp Niethammer Lab

Research

Interdisciplinary approaches to wound healing, inflammation and regeneration.

Research Projects

Featured News

Publications Highlights

People

Philipp Niethammer, PhD

- Cell biologist Philipp Niethammer investigates tissue damage responses with advanced imaging approaches in zebrafish.

- PhD, European Molecular Biology Laboratories & Hamburg University, Germany

- [email protected]

- Email Address

- 212-639-5332

- Office Phone

Members

- Ph.D., Molecular, Cell and Developmental Biology

- BA, New York University

Achievements

- Dorsett L. Spurgeon Distinguished Research Award (2009)

- Louis Gerstner Young Investigator (2012)

- American Asthma Foundation Scholar (2014)

- Louise and Allston Boyer Young Investigator Award (2018)

Open Positions

To learn more about available postdoctoral opportunities, please visit our Career Center

To learn more about compensation and benefits for postdoctoral researchers at MSK, please visit Resources for Postdocs

Career Opportunities

Get in Touch

-

Lab Head Email

-

Office Phone

-

Lab Phone

Disclosures

Members of the MSK Community often work with pharmaceutical, device, biotechnology, and life sciences companies, and other organizations outside of MSK, to find safe and effective cancer treatments, to improve patient care, and to educate the health care community. These activities outside of MSK further our mission, provide productive collaborations, and promote the practical application of scientific discoveries.

MSK requires doctors, faculty members, and leaders to report (“disclose”) the relationships and financial interests they have with external entities. As a commitment to transparency with our community, we make that information available to the public. Not all disclosed interests and relationships present conflicts of interest. MSK reviews all disclosed interests and relationships to assess whether a conflict of interest exists and whether formal COI management is needed.

Philipp Niethammer discloses the following relationships and financial interests:

-

American Association for Anatomy

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated) -

American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated) -

American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB)

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated) -

European Molecular Biology Laboratory

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated) -

European Molecular Biology Organization

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated)

-

Gordon Research Conferences

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated) -

Mount Sinai Health System

Professional Services and Activities -

National University of Singapore

Professional Services and Activities (Uncompensated) -

University of Virginia

Professional Services and Activities

The information published here is a complement to other publicly reported data and is for a specific annual disclosure period. There may be differences between information on this and other public sites as a result of different reporting periods and/or the various ways relationships and financial interests are categorized by organizations that publish such data.

This page and data include information for a specific MSK annual disclosure period (January 1, 2024 through disclosure submission in spring 2025). This data reflects interests that may or may not still exist. This data is updated annually.

Learn more about MSK’s COI policies here. For questions regarding MSK’s COI-related policies and procedures, email MSK’s Compliance Office at [email protected].