The Prasad Jallepalli Lab

Research

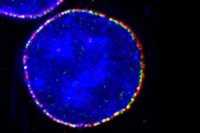

Our laboratory is interested in how human cells accurately duplicate and transmit their chromosomes during each round of division.

Featured News

Publications Highlights

J. Maciejowski, H. Dreschler, K. Grundner-Culemann, E.R. Ballister, J.-A. Rodriguez-Rodriguez, V. Rodriguez-Bravo, M.J.K. Jones, E. Foley, M.A. Lampson, H. Daub, A.D. McAinsh, and P.V. Jallepalli. Mps1 regulates kinetochore-microtubule attachment stability via the Ska complex to ensure error-free chromosome segregation. Dev. Cell 41, 153-156 (2017).

V. Rodriguez-Bravo, J. Maciejowski, J. Corona, H.K. Buch, M.T. Kanemaki, J.V. Shah, and P.V. Jallepalli. Nuclear pores protect genome integrity by assembling a premitotic and Mad1-dependent anaphase inhibitor. Cell 156, 1017-1031 (2014).

People

Prasad Jallepalli, MD, PhD

Member

- Molecular biologist Prasad Jallepalli studies the mechanisms that ensure accurate chromosome transmission in human cells.

- MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

- [email protected]

- Email Address

- 212-639-3252

- Office Phone

Members

- Wesleyan University

Achievements

- Phi Beta Kappa, Harvard University (1992)

- M.D./Ph.D. Fellow, Medical Scientist Training Program, Johns Hopkins University (1992-1999)

- Postdoctoral Fellow, Damon Runyon Cancer Foundation (1999-2002)

- Scholar, V Foundation for Cancer Research (2003)

- Frederick R. Adler Chair for Junior Faculty (2003-2007)

- Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences (2003-2007)

- Louise & Allston Boyer Young Investigator Award (2008)

- Research Scholar, American Cancer Society (2008-2011)

Open Positions

To learn more about available postdoctoral opportunities, please visit our Career Center

To learn more about compensation and benefits for postdoctoral researchers at MSK, please visit Resources for Postdocs

Career Opportunity

Get in Touch

-

Lab Head Email

-

Office Phone

-

Lab Phone

-

Lab Fax

Disclosures

Members of the MSK Community often work with pharmaceutical, device, biotechnology, and life sciences companies, and other organizations outside of MSK, to find safe and effective cancer treatments, to improve patient care, and to educate the health care community. These activities outside of MSK further our mission, provide productive collaborations, and promote the practical application of scientific discoveries.

MSK requires doctors, faculty members, and leaders to report (“disclose”) the relationships and financial interests they have with external entities. As a commitment to transparency with our community, we make that information available to the public. Not all disclosed interests and relationships present conflicts of interest. MSK reviews all disclosed interests and relationships to assess whether a conflict of interest exists and whether formal COI management is needed.

Prasad Jallepalli discloses the following relationships and financial interests:

-

MilliporeSigma

Intellectual Property Rights

The information published here is a complement to other publicly reported data and is for a specific annual disclosure period. There may be differences between information on this and other public sites as a result of different reporting periods and/or the various ways relationships and financial interests are categorized by organizations that publish such data.

This page and data include information for a specific MSK annual disclosure period (January 1, 2024 through disclosure submission in spring 2025). This data reflects interests that may or may not still exist. This data is updated annually.

Learn more about MSK’s COI policies here. For questions regarding MSK’s COI-related policies and procedures, email MSK’s Compliance Office at [email protected].