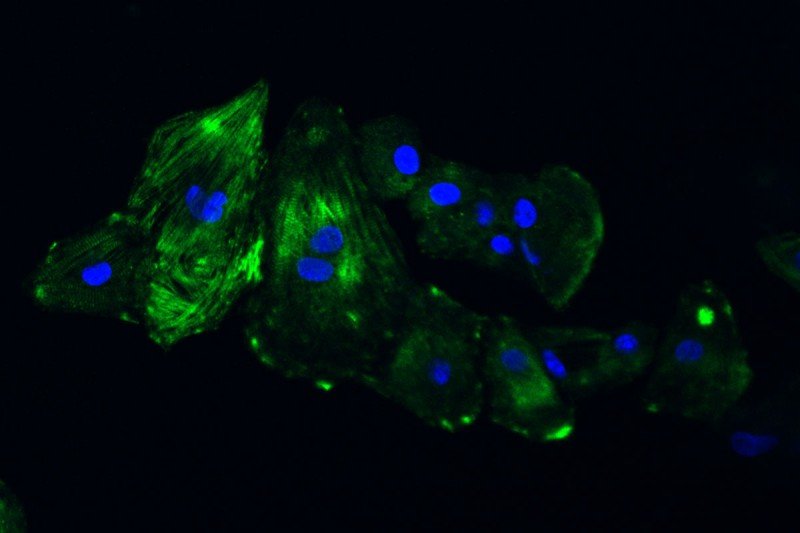

The above image shows cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells) made from a patient’s skin cells.

For people with breast cancer whose cells produce too much of a protein called HER2 — nearly one-quarter of all breast cancer patients — drugs that block HER2 have made a big difference in curing their disease. The most well-known of these therapies is trastuzumab (Herceptin®). It was the first targeted cancer drug ever approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

One side effect of the drug, however, has become a cause of concern. Doctors have observed that more than 10% of people receiving trastuzumab experience heart problems. These include a weakening in the heart muscle’s contraction function, which is responsible for pumping blood throughout the body. A smaller proportion of patients, 2 to 3%, may eventually experience heart failure characterized by shortness of breath and/or swelling. Because of this, experts recommend regular heart monitoring for all patients who are receiving drugs that target HER2, both during and after cancer treatment.

“As cardiologists who focus on taking care of people with cancer, our goal is to optimize the delivery of effective cancer therapy while helping patients avoid potentially life-threatening cardiovascular side effects,” says Richard Steingart, Chief of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Cardiology Service. “We’ve found that if patients have their treatment suspended due to heart problems, even temporarily, it has a negative effect on their cancer prognosis.”

MSK scientists are taking the hunt for new protective methods into the lab. They are using the latest advances in stem cell research to uncover why this relationship exists and to look for ways to thwart it.

Dr. Steingart recently recruited physician-scientist Angel Chan to lead a new research project. Dr. Chan’s group has found a way to essentially create miniature heart muscles in a dish to study them and uncover the connection between trastuzumab and the loss of heart function.

An Unfortunate Coincidence

Trastuzumab is in a class of drugs called monoclonal antibodies. It works by blocking signals from the HER2 protein, which drive the growth of cancer cells. Blocking them with trastuzumab can slow or stop tumor growth.

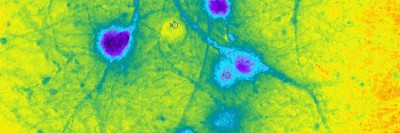

Unfortunately, HER2 is also found in heart cells called cardiomyocytes, which enable the heart to beat. In the cardiomyocytes, HER2 allows cells to repair themselves when they become damaged. Heart damage occurs naturally at the cellular level but can also be made worse by chemotherapy. So if the protein gets blocked by trastuzumab, the heart cells may not be repaired and eventually die.

Dr. Chan, a cardiologist who also has a doctoral degree in materials science and engineering, came to MSK from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where she conducted research using cardiac stem cells to treat heart failure in lab animals. At MSK, she is managing a collaborative effort with investigators at Mount Sinai. “We started this project to bridge the gap between understanding the clinical effects of cancer drugs and determining what goes on in heart muscles at the cellular level,” Dr. Chan explains.

Taking Patient Data Back to the Lab

“MSK has significant amounts of data about the effects of trastuzumab on patients’ cardiovascular health,” she says. “By reviewing their charts, we’re able to see how they fared after treatment.”

Dr. Chan’s team uses skin cells from these patients to create what are called induced pluripotent stem cells. These cells have the ability to develop into any kind of cell in the body and can be grown in a dish. The researchers then expose the cells to certain factors that induce them to become cardiomyocytes. When enough cardiomyocytes develop, they form strips of heart muscle tissue that can be used in a number of experiments.

So far, Dr. Chan and her colleagues have created cardiomyocytes from three MSK patients who experienced heart problems after taking trastuzumab, as well as from three patients who took the drug but didn’t have any heart problems to serve as controls. They are conducting a number of experiments looking at how certain features of the cells are affected when HER2 is blocked. They’re also studying the effect that trastuzumab has on the heart’s ability to send electrical impulses, which is what allows it to beat.

Dr. Chan hopes to eventually develop new diagnostic methods to determine which patients are likely to experience the most severe cardiac side effects from trastuzumab. She also wants to develop new targeted therapies to block those effects in the heart.

Many clinical investigators at MSK are also focused on this problem. Cardiologist Anthony Yu, along with medical oncologist Chau Dang and cardiologist Jennifer Liu, is leading a trial comparing three different methods for assessing heart function in patients receiving trastuzumab. The goal is to determine which method is the most effective.

“MSK’s Cardiology Service is dedicated to finding solutions to this problem,” Dr. Steingart concludes.