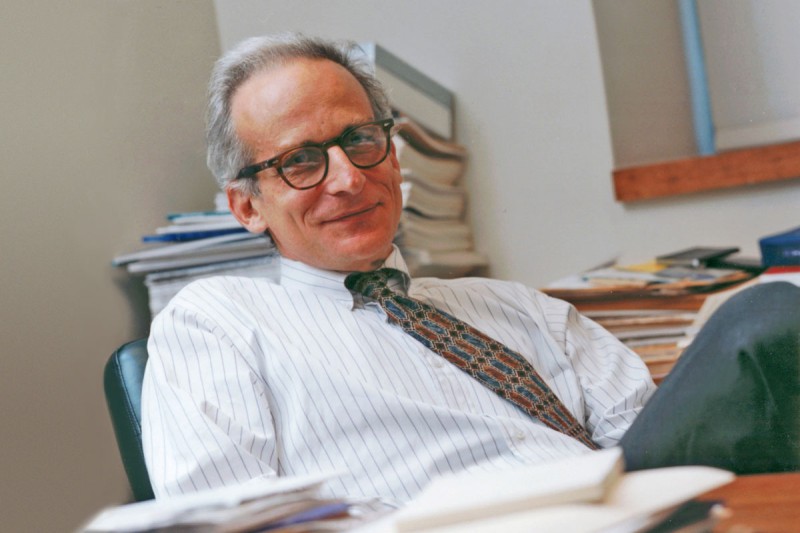

Kent Sepkowitz is an infectious disease specialist and Deputy Physician-in-Chief for Quality and Safety at MSK.

Kent Sepkowitz was 26 years old in 1980 when the first recognized AIDS cases appeared. As a medical intern based in New York City, he had a front row seat for the unfolding crisis that baffled doctors and decimated a generation of gay men, people with hemophilia, IV drug users, and others.

In honor of World AIDS Day on December 1, we spoke with Dr. Sepkowitz about what it was like in those early days, including the role Memorial Sloan Kettering played in caring for people with AIDS. He recounts how in the course of his career, HIV infection changed from a death sentence to a manageable condition for those with access to medicines.

Where were you and what were you doing at the start of the epidemic?

I grew up in Oklahoma, where I also went to college and medical school. I came to New York City in 1980 to be an intern at Roosevelt Hospital, which is now called Sinai West. We started seeing these unusual cases — people with weird chronic pneumonias. The first years of my training were spent asking: “What is this? Why is this happening?” By the time I finished my training, in 1984, a few attending physicians I worked with were getting sick and dying. It felt like the disease was closing in.

We didn’t know the route of transmission then. The virus had not been identified. It was a really scary time.

For the first decade or so, I was a young guy taking care of people my own age who were dying. This was not what I signed up for as a doctor. I thought I’d be taking care of older folks. Some of the patients I saw were friends of friends. So there was that sky-is-falling feeling.

I was very drawn to it though. I decided to pursue infectious disease as a career because it just seemed so important. And it was fascinating too. So I was born into it. My medical career started with HIV.

How did you manage the uncertainty about risk?

You just did. I’ve wondered that too because it came up for me with SARS [severe acute respiratory syndrome] and with Ebola. Healthcare workers were dying from SARS. And with Ebola, they were dropping like flies. I don’t know, you just kind of do your job and hope for the best.

What did you do after your residency at Roosevelt?

I finished my chief residency in 1984. Then I worked in the emergency room at Beth Israel, which is also now Mount Sinai. We saw a lot of IV drug users, and there was a huge number of AIDS cases. The way it would work then is there’d be one or two attending physicians. The patient charts would come in, and the nurses would stack them. You were supposed to take the top chart, but I was always fishing through the pile looking for HIV cases. The gunshot wounds didn’t interest me. The vomiting didn’t interest me. But pneumonia in a 37-year-old was interesting to me. I just kept grabbing those charts, and my brain eventually said, “You should listen to this.”

After four years of ER medicine, I started training in infectious disease at MSK in 1988. I intentionally came to MSK because it was a leading hospital for HIV and because the head of infectious disease at the time was Don Armstrong. He’s one of the giants of that first generation of AIDS experts who were mid-career when HIV hit.

Why was MSK, a cancer hospital, such a hotbed for AIDS treatment?

MSK nurse Melanie Carrow has cared for people with HIV/AIDS since the beginning of the epidemic.

There were several reasons. One was Kaposi sarcoma (KS) [an early AIDS complication that manifested as purple or brown spots on the skin]. Bijan Safai was a dermatologist here at the time and saw a lot of people with KS. And Susan Krown, an immunologist, was the first person to publish on the use of interferon as a treatment for KS.

Also, lymphomas are more common in people with the syndrome, so the lymphoma team got involved.

Probably the biggest reason is that MSK was, up to then, one of the only places that saw and treated things like pneumocystis and toxoplasmosis [opportunistic infections common with AIDS]. That was because these were seen in patients with cancer in the 1960s and 1970s, especially patients with leukemia who had their entire immune systems knocked out from chemotherapy. MSK had 20 years of experience dealing with opportunistic infections when AIDS hit. We were the only ones in town who knew how to treat them.

MSK was also one of the first places that had AZT [azidothymidine, a nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitor]. People were clamoring to get the drug when it became available in 1985 or 1986.

When I arrived in 1988, my outpatient clinic was almost all people with HIV, most on clinical trials. We offered very personalized care. We were lucky to have an amazing nurse, Melanie Carrow, who held the whole operation together. She’s still here, doing the exact same amazing stuff.

When did doctors know that you were onto something with HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy)?

By the time I got here, we were starting to lose faith in AZT. It’s very hard to give. For the first few years, we gave it at a high dose every four hours. Patients would set their alarm at 3 in the morning to wake up to take it. It would give some people maybe a year or two of modest improvement, which was huge at the time. Some people did really well, but for many others, it was disappointing.

As new drugs became available, we began incorporating them. We would try adding DDI [a drug chemically similar to AZT] together with AZT and tried anything we could with a small handful of meds. Then in 1993, nevirapine [a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor] came along, and that seemed to add more oomph. The New York Times published an article on how we were trying to be fair in prioritizing who could get the new drugs.

So there were flickers of hope, and then there were also disappointments. It wasn’t until protease inhibitors came along in 1995 that we started to get cautiously excited. We kept waiting for the bottom to fall out. Patients would have six months of good health, and then even a year of good health. There was no crash and burn as previously. And slowly we thought, Oh, my God, this might really be working. It took several years to trust that feeling. But that was a moment, an incredible once-in-a-lifetime moment.

We also made some mistakes. We didn’t know about IRIS [immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome] when we started giving HAART. This is the syndrome where you give HAART to somebody and they have this huge inflammatory reaction. Their immune system is waking up, and all these bacteria and viruses are sitting around in their system, minding their own business, and you turn on the immune system and the patients get very sick. We couldn’t figure out why. We’d stop the drugs and then start them again. But because we didn’t recognize this syndrome for months or a year even, many people died because we didn’t know how to manage it. I feel so bad about that. We had the drugs, but we didn’t know about the syndrome, didn’t know how to handle things.

Does it now seem surprising that people didn’t think about combining drugs sooner?

We would have but we didn’t have them. As soon as we got a second drug, we added it. At first, we only had AZT. We knew it wasn’t ideal to give just one drug because of the risk that resistance would develop. We’re infectious disease people — combination therapy is our whole game. We’d seen the need for it with tuberculosis. But it just wasn’t an option with HIV at the time.

Is AZT still used?

AZT was a backbone drug for HAART when we first started giving this treatment. But it’s now been pushed out by other drugs that do the same thing but are more potent, less likely to provoke resistance, less toxic, and can be given once a day.

There’s a lot of choices for HAART now — a handful of different once-a-day treatments with various meds rolled into a single pill. It’s sort of unreal to witness how quickly things improved once we had enough different medications to juggle and combine. Many people now who tolerate the drugs can expect a normal lifespan.