Lymphedema, a painful swelling in the arms or legs, is one of the most unpleasant complications of cancer treatment. It develops when surgery or radiation causes damage to the lymphatic system, a network of vessels that filter and clear fluid from the tissues.

Lymphedema most commonly occurs when some or all of the lymph nodes under the arm are removed as part of treatment for breast cancer, a procedure called lymph node dissection. When severe, lymphedema can cause great discomfort, hamper day-to-day activity, and increase the risk of infection. There is no cure for this condition, which can last for years and even decades.

Memorial Sloan Kettering has a lymphedema laboratory dedicated to changing that. For the last decade, Babak Mehrara, Chief of the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgical Service, has led a team studying how lymphedema develops and progresses. These researchers, headed by senior research scientist Raghu Kataru, work closely with MSK doctors to look for new treatments to prevent or reverse the condition.

Lymphedema is a complex disease that has long been poorly understood. It doesn’t occur immediately after surgery but usually eight to 12 months later. “That suggests that some intervening step must occur that causes lymphedema to develop in certain people,” Dr. Mehrara explains.

Further, the majority of people who have lymph nodes removed never develop lymphedema. Certain factors place a person at higher risk, such as having a large number of nodes removed or being overweight. But researchers needed a clearer picture of what causes the condition to occur.

Selective Immune Suppression

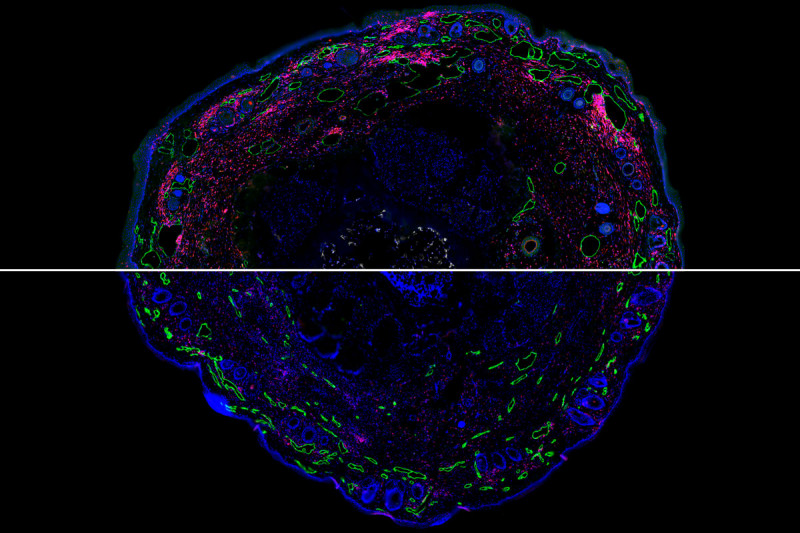

Researchers have known for decades that damage to the lymphatic system results in chronic inflammation. Dr. Mehrara’s research has more recently shown that this inflammatory reaction is a key step in the development of lymphedema. Although it is not clear why only some people have this response, the finding has opened up the possibility that stopping the immune cells could prevent lymphedema.

The body needs inflammation to protect against infection and repair wounds, so blocking all immune cells involved in this process is not an option. But in 2009, Dr. Mehrara’s team showed that lymphedema–associated inflammation was driven by a specific group of immune cells called Th2 cells.

“Th2 cells are mainly important for fighting off parasitic infections, and we don’t have a lot of parasites in Western countries,” Dr. Mehrara says. “We thought that selectively inhibiting these immune cells might prevent or inhibit lymphedema without putting the patient at risk.”

In 2017, Dr. Mehrara and colleagues demonstrated that tacrolimus (Prograf®), could tamp down Th2 activity. The drug, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, is used for conditions like eczema and works by weakening the skin’s immune defense. It is applied directly to the skin and was shown to prevent and even reverse lymphedema in mice.

“Now that we’ve shown that this strategy can work in animals, we’re trying to translate this work into clinical trials in humans with lymphedema,” Dr. Mehrara says.

A Fertile Research Environment

Dr. Mehrara explains that the environment at MSK enables a collaborative approach to lymphedema that is unmatched.

“There are no other cancer centers with a dedicated lymphedema laboratory and a busy clinical lymphedema surgery program,” he says. “The synergy between our basic science research and our clinical programs enables us to rapidly translate our research from the bench to the bedside and validate our work in the laboratory.”