Lung adenocarcinoma, the most common form of lung cancer in the United States, can be difficult to cure unless diagnosed at an early stage. Surgery is effective at removing early-stage tumors, but more than half of patients with stage 2 or 3 disease have a recurrence of their cancer elsewhere in the body. Because of this, people with lung cancer usually receive chemotherapy after surgery to try to kill any undetected tumor cells.

However, only 5% to 15% of patients with lung cancer benefit from chemotherapy after surgery. This means that the vast majority endure months of chemotherapy treatment — and its side effects — without extending their survival. Unfortunately, there has been no way to know ahead of time which patients will respond to treatment.

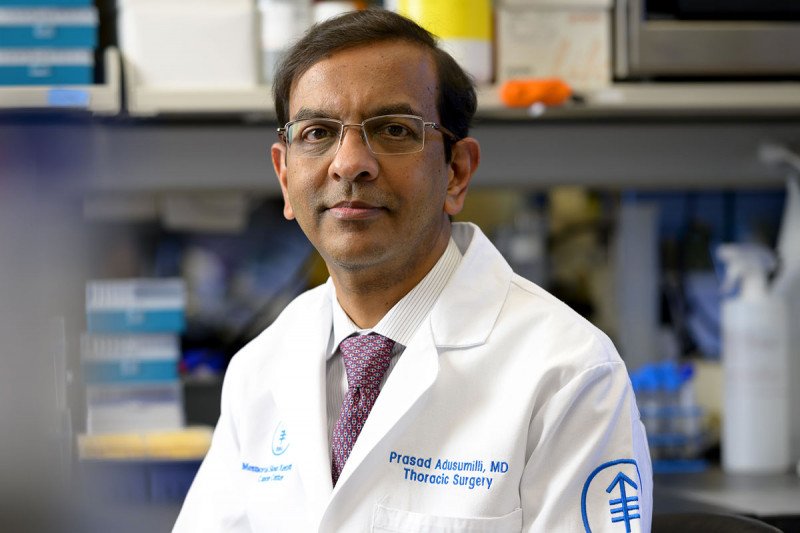

“In many patients, the cancer cells have spread beyond the primary tumor and are hiding somewhere in the body,” says Prasad Adusumilli, a thoracic surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “But there is no way to know for sure if this is the case. We have had to give chemotherapy treatment to nearly everyone, often without much benefit.”

Through recent research efforts, Dr. Adusumilli and his colleagues at MSK have found a clue in the form of a biomarker that could help identify patients who will respond to chemotherapy — as well as suggesting that the immune system is involved in this response.

By studying lung cancer tumors in the lab, they discovered that high levels of a protein called PD-L1 were associated with patients living longer after chemotherapy. The elevated levels were found both in the cancer cells and in a type of immune cell called a tumor-associated macrophage.

When the researchers looked at the patients’ clinical records, they found that patients with increased PD-L1 had a much better chance of surviving past two years (95%) than those without this biomarker (55%). After five years, the difference in survival was even more striking: 75% of patients with high expression of PD-L1 were still alive, compared with only 20% of patients with normal expression. The study reporting this work was recently published in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

This finding about PD-L1 expression could improve treatment for people with lung cancer, and it also provides evidence that chemotherapy works, in part, by enlisting the immune system to help fight the cancer.

“This could be an important step toward finding better ways to combine chemotherapy and immunotherapy for patients with stage 2 and 3 lung cancer,” Dr. Adusumilli says.

Learning from the Cells Around the Tumor

The researchers studied nearly 400 lung adenocarcinoma tumor samples from patients treated at MSK. The team hypothesized that studying the cells in and around the primary tumor could provide insights into how lung cancer cells take root and grow in new locations.

Researchers already knew that tumors survive, in part, by surrounding themselves with immune cells that control the actions of other immune cells. These suppressor cells act as a mask that hides the tumor from the immune system. The tumor-associated macrophages make up an essential part of this mask, known as the tumor microenvironment. Lung cancer cells that spread from the primary tumor — typically to the bone, brain, or liver — likewise seem to be able to evade attacks from the immune system, lurking undetected before eventually multiplying.

“We study the microenvironment these cancer cells create for themselves in the primary tumor to figure out how they establish themselves at the metastatic site,” Dr. Adusumilli says. “It’s like the cancer cells are building a house in the new location, so we are looking at the kind of bricks and mortar they use at the first location.”

High levels of PD-L1, Dr. Adusumilli explains, indicate that the immune system recognized the cancer and mounted an attack. Expression of PD-L1 was then increased to tamp down the response from the immune system, resulting in the creation of the mask that hides the tumor. This is presumably true for the primary tumor site as well at as metastatic sites.

Chemotherapy appears to change all that.

“We think that, in a cohort of patients, chemotherapy removes the mask, tilting the balance so that the attacking immune cells are able to destroy the cancer,” Dr. Adusumilli says.

The researchers are planning a new study in which they will collect blood and lymph node samples, in addition to tumor samples, to try to get a clearer picture of the actions of chemotherapy in patients who benefit from this treatment. If removing the mask is all it takes for the immune system to take over, shorter courses of chemotherapy might be just as effective as current practice.

“Most patients with lung cancer are older than 65, and chemotherapy can cause deafness, kidney damage, or nerve damage,” Dr. Adusumilli says. “Reducing the amount of chemotherapy we give could markedly improve the quality of life of these patients.”

Better Combination Treatments

The study provides important insights into immunotherapy, as well as chemotherapy. New immunotherapy treatments have shown promise for lung cancer, but, like chemotherapy, they work in only a fraction of patients. Researchers have been trying to combine the two treatments to potentially harness their synergy and figure out who will benefit from these therapies.

This finding about PD-L1 expression could improve treatment for people with lung cancer, and it also provides evidence that chemotherapy works, in part, by enlisting the immune system to help fight the cancer.

“The next step of this research is to use this knowledge to determine how to combine these therapies in a strategic way for each individual patient — such as how much of each treatment to give and in what order,” Dr. Adusumilli says.

He cites the importance of philanthropic support from the Joanne and John Dallepezze Foundation. “Pharmaceutical companies tend to support trials investigating a therapy,” Dr. Adusumilli says. “At MSK, though, philanthropy is essential for these kinds of biological insights that we make by studying tumor samples that usually are otherwise discarded.”

He also points to MSK’s “special culture” of obtaining permission from all patients who are operated on to store their tumors for future study — enabling researchers to make important discoveries years later. “We had access to thousands of tumors we could analyze, allowing us to focus on each specific type of lung cancer,” he says. “By diving deep and analyzing large sets of tumors, along with the long-term follow-up of patients, we are able to make important biological observations that are being translated to new treatment paradigms. That’s an important way MSK distinguishes itself as a leader in lung cancer research.”

- Adenocarcinoma is the most common form of lung cancer.

- Chemotherapy after surgery often doesn’t prevent lung adenocarcinoma from returning.

- A new finding shows that chemotherapy has a “bystander effect” in lung adenocarcinoma and influences the immune system.

- This new finding could guide the development of treatments that combine chemotherapy and immunotherapy and may also help identify which patients with lung adenocarcinoma will respond to chemotherapy.