Life is about choices. That’s as true for cells as it is for people.

Every cell in our bodies, from the retinal cells in our eyes to the skin cells in our toes, has taken a journey filled with alternate paths and roads not taken. Deciphering what points cells in one direction or another is a main goal of developmental biology.

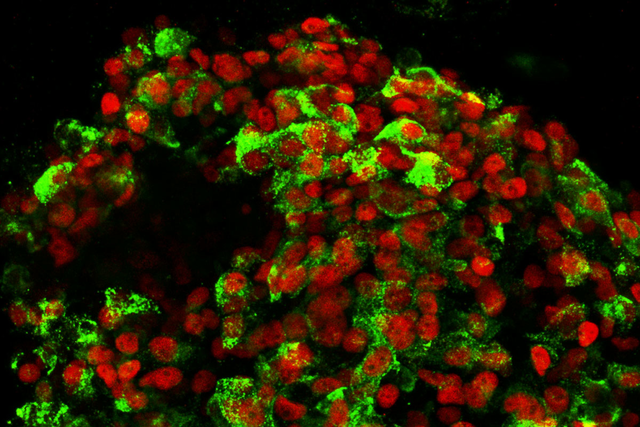

One of the earliest and most consequential decisions a cell makes is whether to become part of the endoderm, one of the three germ layers that make up an early embryo. The endoderm gives rise to the organs in the chest and gut, such as the lungs, stomach, and pancreas.

A new study led by a team of scientists at the Sloan Kettering Institute has uncovered five genes previously not known to influence endoderm development.

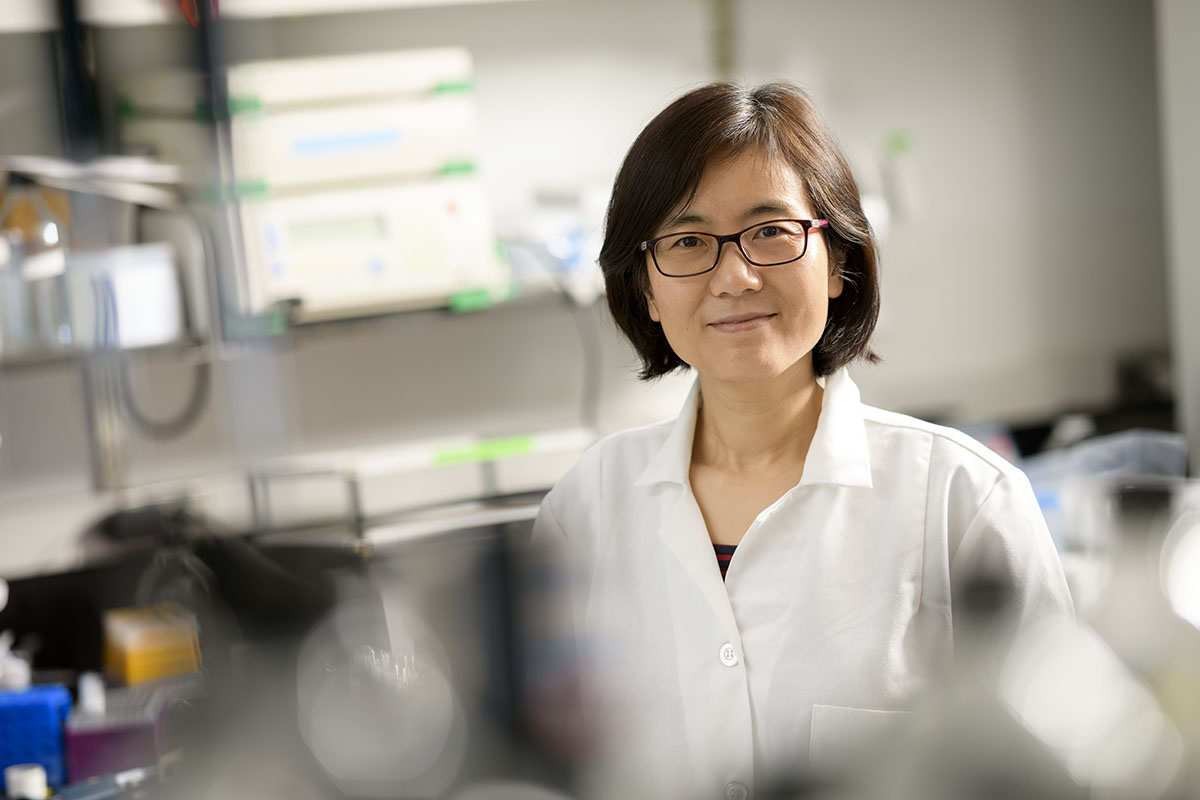

The team, including developmental biologist Danwei Huangfu and Gerstner Sloan Kettering student Qing Li, used CRISPR to make the discovery. This genome-editing tool is akin to a pair of DNA scissors. By systematically cutting every gene in the genome of an embryonic stem cell one by one, they were able to pinpoint the signals that influence this crucial decision.

Unlike the signals that push cells toward a new fate, the ones the SKI investigators found pull in the other direction. Dr. Huangfu likens it to a person deciding whether to go to work or not.

“One factor that could affect his decision is how much he loves his job. This would provide a clear push in one direction. But another factor might be a competing desire to stay at home with a new baby that would pull in the other direction,” Dr. Huangfu explains.

The signals she and her colleagues found operate more like the latter — as factors that prevent cells from proceeding toward endoderm development.

The five genes they uncovered with CRISPR encode proteins that affect how strongly other proteins bind to DNA. These proteins pull the cell toward a pluripotent (noncommitted) state. By blocking these pull signals with chemicals, the investigators found that they could hasten a cell’s decision to become part of the endoderm. The results were reported on May 20 in the journal Nature Genetics.

Dr. Huangfu’s team is ultimately interested in mapping the complete sequence of decisions that a cell must make to become a particular type of pancreas cell, the one that makes insulin. Having that recipe would greatly enhance the prospects for regenerative medicine, to repair a damaged pancreas, for example.