Once reserved for high-risk pregnancies, noninvasive prenatal tests (NIPTs) that screen for genetic abnormalities have been the standard of care since 2020. Most pregnant women — some 2 million a year — elect to have the test.

Now a new study has found that in some cases, NIPT results may be normal for the baby but pick up something serious in the mother: cancer.

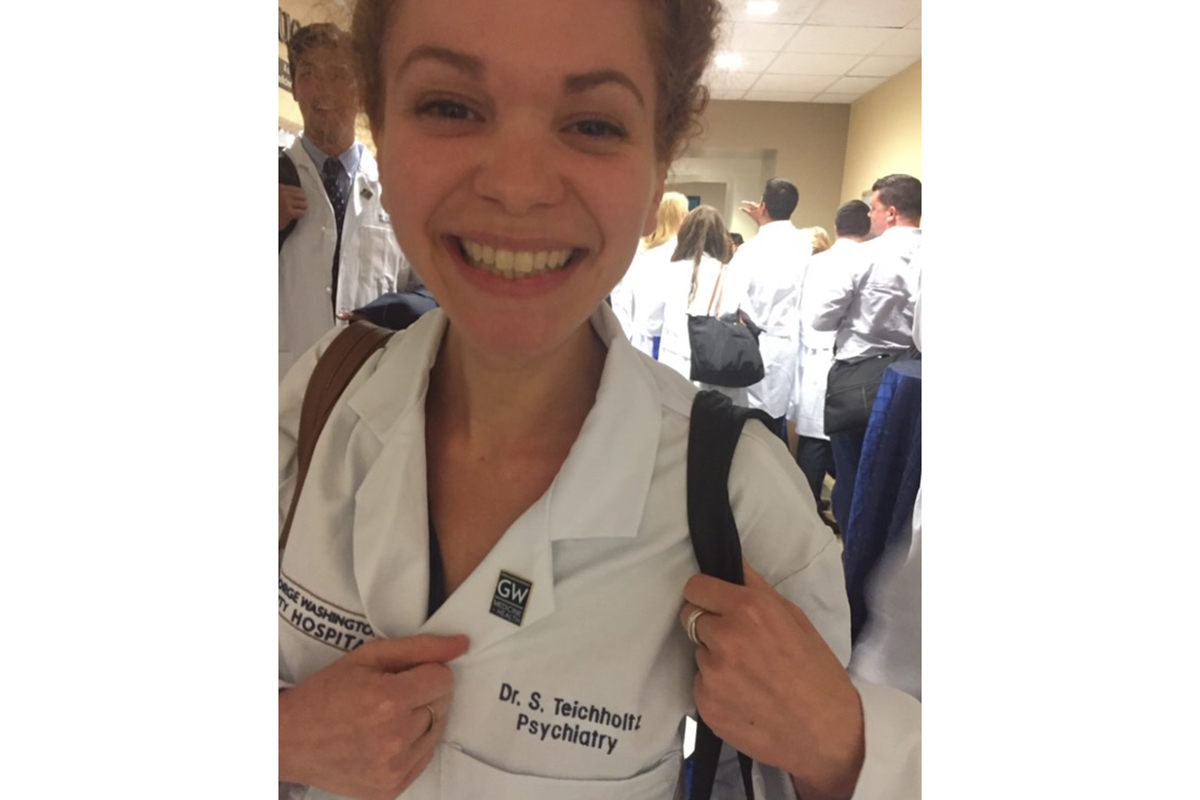

“Without this prenatal test and the study that focused on figuring out what the test results meant, I can say for certain that I would probably be dead now, or in hospice care,” says Sara Teichholtz, MD, who was 35 when a prenatal test came back with “nonreportable” findings, meaning they were ambiguous.

Further testing resulted in a shocking diagnosis: Dr. Teichholtz had cholangiocarcinoma, a rare, aggressive type of tumor in her liver that has a notoriously poor prognosis. According to the American Cancer Society, 10% of patients with cholangiocarcinoma are alive five years after diagnosis. There are no early symptoms or screening tests for this cancer, and it’s usually caught in later stages when it’s more difficult to treat.

Thankfully for Dr. Teichholtz, nearly three years after her diagnosis and treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), she has no evidence of disease.

She is just one of the patients who participated in a study by the National Institutes of Health that found nearly half of pregnant women with nonreportable results from prenatal testing turned out to have cancer. And she is a co-author in her own case study published in June in the journal JCO Precision Oncology. This research illustrates the promise of blood tests to detect cancer at its earliest stages.

In the paper, Dr. Teichholtz shared her own perspective. “Despite my medical training, navigating the healthcare system with an unknown cancer diagnosis made me feel alone and scared,” she wrote. “I am forever changed in my role as a physician and forever grateful in my role as a patient.”

NIPT Is a Type of Liquid Biopsy That Measures cfDNA in Mother and Fetus

The NIPT that Dr. Teichholtz had is a blood test, also called a liquid biopsy, given to women early in pregnancy. It screens the fetus for genetic and chromosomal abnormalities like Down syndrome.

NIPT works by examining small bits of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from the fetus that are floating in the mother’s bloodstream. Because NIPT analyzes both fetal and maternal cfDNA, it may also detect a genetic abnormality like cancer in the mother. This is what happened to Dr. Teichholtz.

NIH Study Identifies Cancer in Almost Half of Nonreportable Findings From NIPT

Soon after receiving her prenatal test results, Dr. Teichholtz learned about a study at the National Institutes of Health called IDENTIFY (Incidental Detection of Maternal Neoplasia through Non-Invasive cfDNA). Its aim was to figure out the meaning of nonreportable findings, which happen in about 1 out of 8,000 NIPT tests.

In those pregnant women with ambiguous NIPT results, 52 out of 107 (49%) wound up being diagnosed with cancer.

To get to the bottom of her results, Dr. Teichholtz underwent additional tests, including a full-body MRI scan, which detected a tumor in her liver. A follow-up tissue biopsy revealed it was cholangiocarcinoma.

“I had no symptoms and no risk factors,” Dr. Teichholtz says. “I had just finished a year of specialized training in palliative care, working with cancer patients who were at the end of life. I thought, ‘I know what cancer looks like, and I don’t have it.’ ”

Traveling for MSK’s Expertise in Liver Cancer Treatment

Dr. Teichholtz and her husband traveled from their home near Washington, D.C., to meet with doctors at several cancer centers. But after consulting with hepatopancreatobiliary surgeon William Jarnagin, MD, FACS, and gastrointestinal medical oncologist and early drug development specialist James Harding, MD, it was obvious to Dr. Teichholtz that MSK was the right place to get treated.

“We knew that choosing the best surgeon was the most important thing we could do, and everyone we talked to mentioned Dr. Jarnagin,” she says. “It was worth traveling to be treated at MSK.”

Unfortunately, she would have to terminate her pregnancy in order to receive cancer treatment. “That was hard, because it was very much wanted,” says Dr. Teichholtz, who already had one child, a son who is now 4.

Within 10 days, she began treatment for her cancer. First, Dr. Jarnagin performed an operation to remove the left side of her liver, her gallbladder, and surrounding lymph nodes. He determined the cancer was stage 2. He also put in a hepatic artery infusion (HAI) pump, which could be used to deliver chemotherapy directly to the liver.

“These pumps can be very effective at shrinking tumors in patients whose colorectal cancer has spread to the liver,” Dr. Jarnagin says. “Their use in cancers like cholangiocarcinoma in the post-surgery setting is still experimental, but something we plan to study.”

As soon as she recovered from surgery, she started regular systemic chemotherapy. Because tests revealed that her tumor had a signature called a mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd), she also received immunotherapy with a drug called a checkpoint inhibitor.

“Dr. Harding told me because I was young and healthy, he was going to give me a very aggressive treatment,” Dr. Teichholtz says.

It worked. Today she is cancer free. Regular scans and other tests show no signs of the cancer returning.

“My hope is that our quick and aggressive interventions will help prevent the cancer from coming back,” Dr. Harding says.

The Potential of Liquid Biopsies for Cancer Screening

After completing treatment, Dr. Teichholtz and her team decided to publish her story as a case study. It’s unusual for the patient’s experience to be so thoroughly described in a research paper, but because she is a doctor, it made sense to her and the rest of the team.

“This case highlights the unique and important connection between fetal medicine and cancer care,” Dr. Harding says. “It also highlights the emerging role of cfDNA in detecting early cancers.”

Dr. Jarnagin adds, “The holy grail in cancer is to be able to determine that someone has cancer with just a blood test. The fact that cholangiocarcinoma was detected with a prenatal test makes this case unique.”

More recently, Dr. Harding published a study in JCO Precision Oncology that found about 25% of patients with biliary tract cancers had mutations that could guide the use of precision therapies. Importantly, more than one-third of these mutations could be detected with the liquid biopsy test MSK-ACCESS® alone. “This illustrates how cfDNA can be used to detect mutations, predict recurrence, and define resistance,” Dr. Harding says.

Learn how MSK is researching the use of liquid biopsies to detect and treat cancer.

Today, Dr. Teichholtz has completed her medical training and works as a psychiatrist. The hepatic artery pump is still in her body in case her cancer comes back, but so far, her care team hasn’t needed to use it.

“I’m so grateful for MSK and for the IDENTIFY study, and I’m excited to be able to share my story,” she says. “I’m very interested to see where this research goes in terms of screening for and monitoring cancer.”