At this year’s Convocation, which is the highlight of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s academic efforts, Sloan Kettering Institute postdoctoral fellow Cornelius Taabazuing was honored with a prestigious award — the 2021 Tri-Institutional (Tri-I) Breakout Award for Junior Investigators. He shared the recognition with another SKI postdoctoral fellow, Wouter Karthaus.

The Tri-I awards are given annually to up to six outstanding postdoctoral fellows at Memorial Sloan Kettering, Weill Cornell Medicine, and The Rockefeller University.

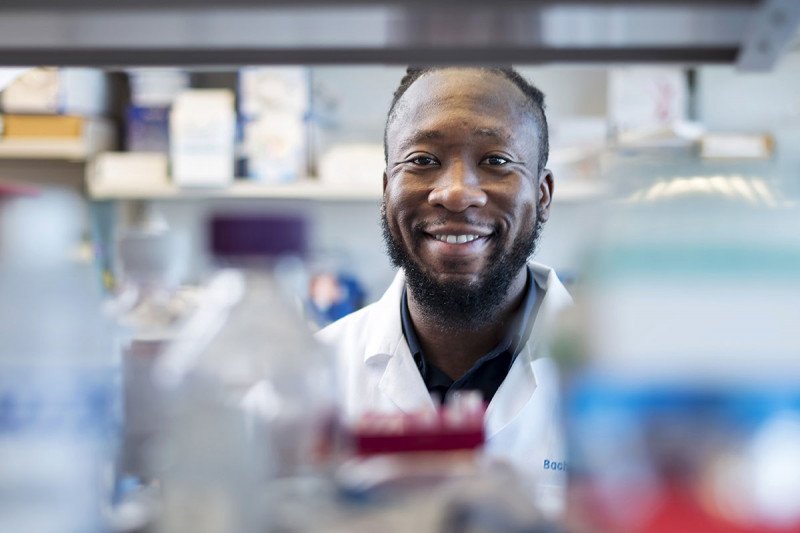

Dr. Taabazuing was honored for his research using applications of cancer and chemical biology to study mechanisms that are a fundamental component of the innate immune system. He conducted his work in the lab of Daniel Bachovchin.

Dr. Taabazuing recently sat down to talk about himself and his work.

Does your family have a scientific background?

Yes, but maybe not in the traditional sense we think of — they are not researchers. My mom is a nurse, my brother is a pathologist, one of my aunts is a doctor, and another aunt and cousin are nurses.

I was born in a village in Ghana, in West Africa, and English was not my first language. We came to America when I was 9 years old. If my parents stayed in Africa, I may not have had the opportunities that I have today. I may not have found out that I have the ability to be a good biomedical researcher. In Ghana, the resources are geared toward research for necessities, such as producing clean water.

My point is that lived experience means a lot. Everybody is capable of many things. But unless you get the opportunities to try things out, you can never know if it’s a strength for you.

What were your formative experiences in science?

In high school, I took chemistry, physics, and biology. I’ll never forget in honors biology when we learned about neurotransmission — how nerve cells use chemicals to communicate across synapses. I found it fascinating.

I attended the University of Massachusetts, Amherst for both undergrad and graduate school. I was fortunate to have great mentors who were not just teachers, including Justin Fermann and Zane Barlow. The very first day of Dr. Fermann’s general chemistry class, he walked in with two balloons. One he had inflated himself, and the other was filled with hydrogen gas. He popped both. Seeing the flames from the hydrogen balloon at nine in the morning showed me how fun chemistry could be. That class helped spark my interest in science. Dr. Barlow encouraged me to go into laboratory research, which I found I really liked.

After college, I had the rare opportunity to work in Tom Cech’s lab at the University of Colorado, through a Howard Hughes Medical Institute program. He shared a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of the catalytic properties of RNA — that RNA could cut strands of itself. In his lab, we studied how telomeres are maintained, which are the end of chromosomes. I enjoyed it immensely. These mentors urged me to go to graduate school, where my excellent advisor was Michael Knapp.

After earning your PhD in biological chemistry, why did you come to MSK as a postgraduate fellow, working in the lab of Daniel Bachovchin?

I guess it was kind of serendipity. Initially, I was interested in epigenetics and finding biomarkers. When I started interviewing for postdoc positions, Dan Bachovchin had so much energy and enthusiasm that it was infectious. That drew me to the field. I had some background in the areas we were focusing on from my experience in other labs. And I was really interested in the fact that we were working with the immune system, which is so important to human health.

I found that Dan is an incredibly supportive mentor. He is one of the most creative scientists that I’ve had the pleasure of interacting with. He’s invested in the success of his mentees, and he provides good, honest feedback.

My lab colleagues are an incredibly collaborative family. They help make MSK a wonderful place to work.

I’m humbled and honored to win the Tri-I award because it’s a validation of all the hard work we’ve put in and recognizes meaningful contributions that I hope will move human health forward.

I also want to thank the scientists who created this award — Dr. Charles Sawyers of MSK, Dr. Lewis Cantley of Weill Cornell Medicine, and Dr. Cori Bargmann of The Rockefeller University. Their support for junior investigators says a lot about the commitment here to encourage the next generation.

What did you learn from the work recognized by the Tri-I Breakout prize?

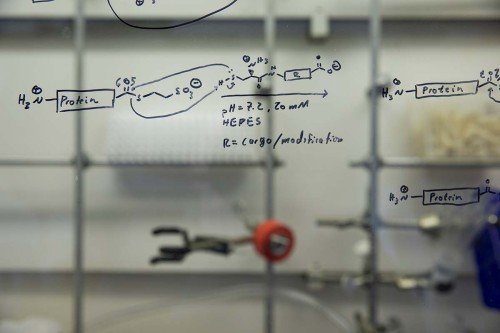

One of the big questions our lab has been studying involves cell death. This is a highly regulated process. But the mechanism that regulates the process is not well understood.

In particular, I study a type of cell death called pyroptosis that activates the immune system. One of the key questions that we had when I started is if you take away some of the machinery involved in this process, what happens to the cell death mechanism?

What we discovered is that there is a key protein that needs to be cleaved or processed in order to cause this immune-stimulatory cell death. If you take that away, the cell is still going to die, but it’s going to die in a different way — called apoptosis — that is not going to stimulate the immune system.

What is also noteworthy is that there are special receptors that cause this cell death. And we have a drug that activates these receptors. We discovered the mechanism of how these receptors respond to this drug and thus how they can be activated for therapeutic purposes.

What’s next for you in science?

After a lot of consideration, the next step in my career is becoming an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, where I will run my own lab. I have learned so much from Dan about how to run a lab, and I’m so grateful for that.

My ongoing work will continue to focus on the immune system, which is really our best line of defense against pathogens and could be our most important weapon in terms of biomedical research.

What do you do outside the lab?

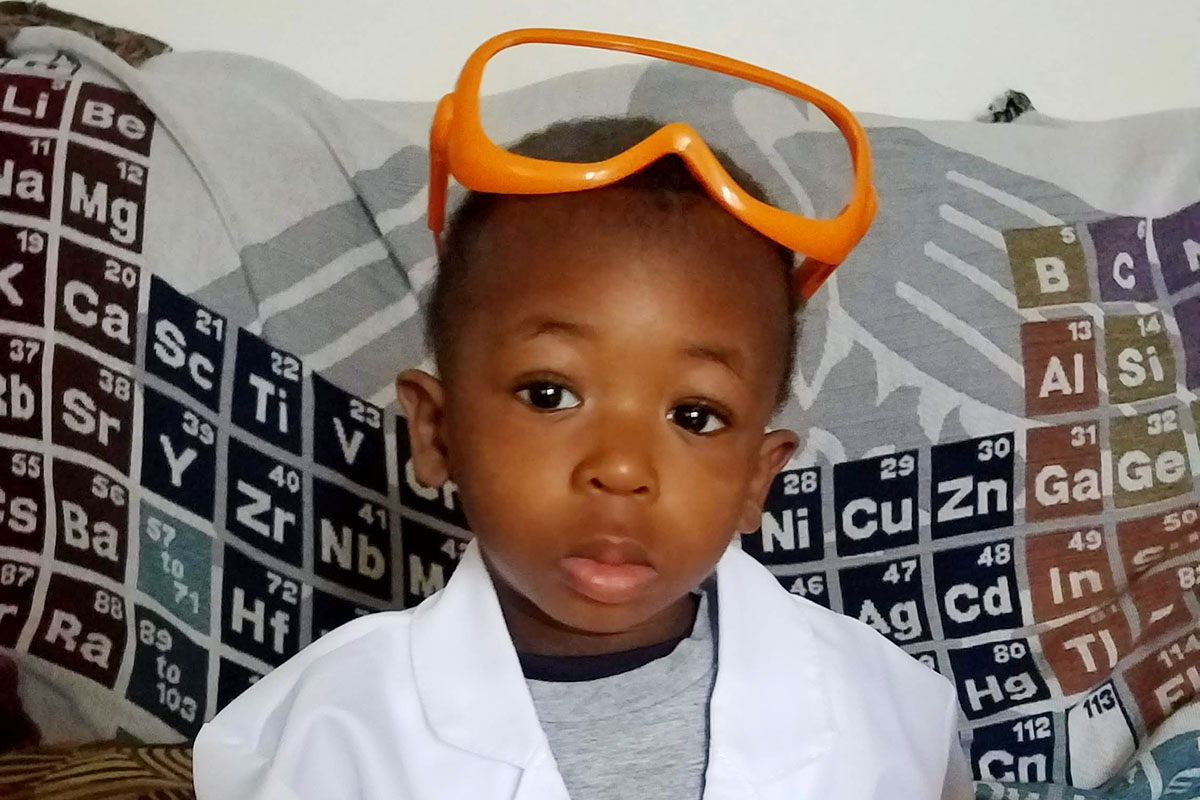

I enjoy playing sports, music, and food. And my 3-year-old son keeps me busy. He asks what I’m doing when he sees me working on the computer. I tell him “Daddy is a scientist. That’s what I do for a living.” For Halloween, we got him a lab coat and little pipettes. So, he’ll definitely be exposed to science, which I think is so important.

That’s what I try to do with outreach efforts I’m involved in, where I talk to middle school, high school, and early college students. I tell them there are people that look like us in science. Seeing people from underrepresented groups in science is crucial. And I know how important representation is as a person progresses in their career, where representation tends to get smaller and smaller.

I want these young people to know that if they take a similar path as me, I’m here for them as a resource.