This guide from Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) can help answer your questions about pancreatic cancer. It’s based on MSK’s strong expertise in treating pancreatic cancer and our credentials as a National Pancreas Foundation Center of Excellence.

You may have just learned you have pancreatic cancer, or are worried you have it. It’s common to have questions. How do you know if you have pancreatic cancer? What causes pancreatic cancer? What’s the best hospital for treating pancreatic cancer?

About MSK’s guide to pancreatic cancer

This guide can support you and your loved ones as you learn more about this disease. We share expert information about pancreatic cancer symptoms and the latest treatments. We have information about pancreatic cancer research studies, also known as clinical trials, that you may be able to join.

Who is this disease guide for?

-

You’re waiting to learn if you have cancer

This guide gives you information about pancreatic cancer so you’re better prepared. If you want to know right away if you have cancer, we have information about MSK’s rapid diagnosis program. -

You want a second opinion

This guide explains new treatments for pancreatic cancer. Learning about them can help you decide if you want a second opinion. MSK’s experts offer second opinions about both diagnosis and treatment options, no matter where you live. -

You’re worried about your current treatment plan

This guide can help you learn about other treatment options. MSK experts only use the latest treatments for pancreatic cancer, some only offered at MSK and very few other hospitals. -

You’re worried about your genetic risk for cancer

This guide can help you learn about your risk for pancreatic cancer. We offer cancer genetic risk assessments to see if you’re at higher risk for some cancers. About 10 out of every 100 cases of pancreatic cancer are from inherited genes passed on from parents to children. -

You’re a caregiver to someone who has cancer

We have information about how to support a loved one who has cancer, even if they’re not an MSK patient. At MSK, supporting caregivers is as important as caring for people with cancer.

Where is the pancreas and what does it do?

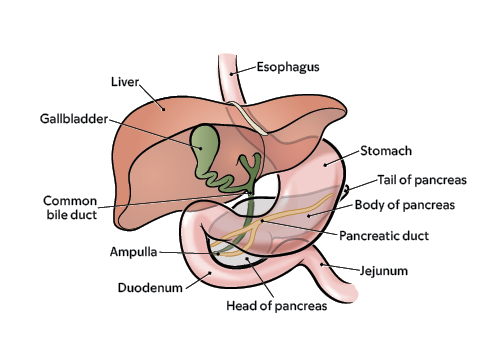

The pancreas is a small gland. It’s located in your abdomen (belly) between your stomach and intestines.

The main job of the pancreas is to make enzymes, a kind of protein that helps you digest food. These enzymes are made by a type of cell called an exocrine cell. Most of your pancreas is made up of exocrine cells.

A very small part of the pancreas is made of endocrine cells. These cells make hormones, including insulin, that control the level of sugar in your blood.

Pancreatic tumors start in either exocrine or endocrine cells. Most pancreatic cancers are exocrine tumors, not neuroendocrine tumors.

Types of pancreatic tumors

There are about 20 different types of tumors that can grow in the pancreas. Exocrine pancreatic cancer tumors are the most common. More than 9 out of every 10 cases of pancreatic cancer are exocrine tumors.

The most common kind is adenocarcinoma. Others are:

- Acinar cell carcinoma

- Intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

- Mucinous cystic neoplasm

Neuroendocrine pancreatic cancer tumors are less common. Fewer than 1 out of every 10 cases of pancreatic cancer are neuroendocrine tumors. They include pancreatic neuroendocrine (islet cell) tumors.

What makes pancreatic cancer so hard to treat and deadly?

How pancreatic cancer spreads

The pancreas is deep in the body. That makes it harder for your healthcare provider to see or feel a tumor during regular exams.

There often are no symptoms of early pancreatic cancer. Tumors can grow large and spread to healthy organs before there are signs of the disease.

As a pancreatic tumor grows, it can spread to nearby organs, such as the bile duct, intestines, or stomach. It also can spread to nearby blood vessels.

Pancreatic tumor cells also can break away. These cells can spread to the lymph nodes, liver, or somewhere else in the abdomen (belly).

Pancreatic cancer is not the most common cancer, but it’s deadly

Pancreatic cancer is not that common, with about 64,000 cases diagnosed each year in the United States. The number of new cases is rising.

There are no recommended screening tests for people at average risk for pancreatic cancer. That makes it harder to catch this cancer early, before it spreads.

Pancreatic cancer is hard to cure.

The 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer has improved in recent years because of better treatments and diagnosis. But it’s still low at around 12%. That means out of every 100 people who get pancreatic cancer, only 12 will be alive 5 years later.

The disease rarely causes symptoms in its early stages. It’s often diagnosed only after it metastasized (spread) from the pancreas to other parts of the body. After it spreads it’s much harder to treat.

Why should I choose Memorial Sloan Kettering to treat pancreatic cancer?

MSK’s team of pancreatic cancer experts

MSK’s team of pancreatic cancer experts is among the nation’s largest. We’re a leading hospital for pancreatic cancer care and research.

Our surgeons operate on about 350 people with pancreatic cancer a year. Our oncologists (cancer doctors) and other subspecialists treat about 850 people a year. That’s among the highest volumes of pancreatic cancer cases in both New York City and the country.

MSK is home to the David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research (CPCR). Its mission is to offer the latest pancreatic cancer treatments and resources while supporting your physical and emotional well-being.

Research excellence

The David M. Rubenstein Center of Pancreatic Research is finding new ways to treat pancreatic cancer through research studies, also known as clinical trials. We led the first clinical trial to test mRNA vaccines as a possible new treatment for pancreatic cancer. The vaccine trains the body to protect itself against its own cancer cells.

National center of excellence

As a National Pancreas Foundation Centers of Excellence, MSK offers the best possible treatment results to give you a better quality of life.

Being named a NPF Center of Excellence means MSK:

- Passed a very strict review of our doctors.

- Offers many programs to support people who have pancreatic cancer. This includes pain management and symptom control, counseling, nutrition, integrative medicine, rehabilitation, pre-habilitation, and other services.

- Shows excellence in our clinical trials as we test new treatments for pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cyst surveillance

MSK’s Pancreatic Cyst Surveillance Program is one of the largest in the country. It monitors pancreatic cysts and has provided treatment for pancreatic cysts for more than 5,000 people. Each year, MSK sees more than 300 new patients who have cysts in their pancreas.

Learn about our Health Information Policy.