Brain tumors are among the deadliest and most difficult cancers to treat. But the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has now approved a new drug that slows the growth of low-grade diffuse gliomas with a certain gene mutation.

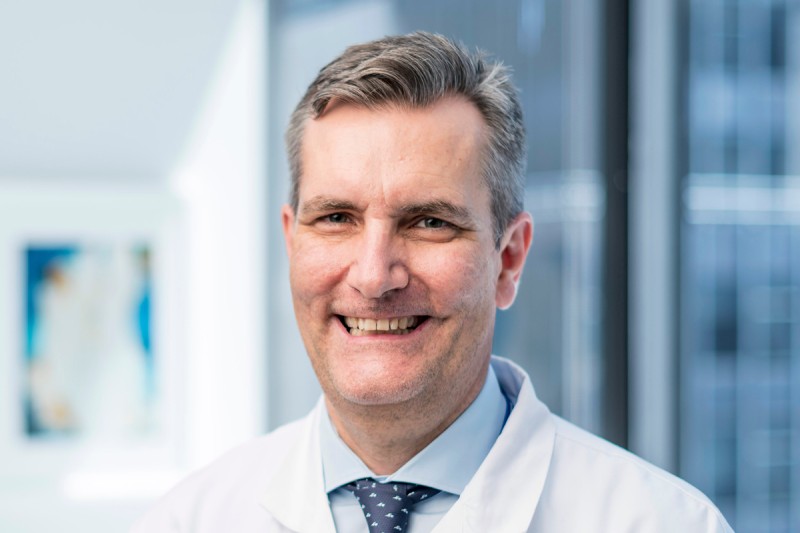

“This represents the first new treatment option for low-grade diffuse glioma in more than 20 years — and the first molecularly targeted therapy specifically developed for this disease,” says Ingo Mellinghoff, MD, FACP, Chair of the Department of Neurology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK).

Dr. Mellinghoff led the clinical trial demonstrating the drug’s potential. Results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2023.

“This therapy could be a huge benefit to many people,” he says. “Even though we call them low-grade, these tumors are far from a low-grade problem. They are incurable.”

The drug, vorasidenib, targets a mutation in IDH genes, which are present in 80% of low-grade gliomas. IDH-mutant gliomas make up about 20% of diffuse gliomas in adults, by far the most common malignant primary brain tumors.

Promising Phase 3 Clinical Trial Results Treating Glioma

In a phase 3 clinical trial of people with low-grade (grade 2) gliomas containing an IDH mutation, vorasidenib significantly slowed tumor growth — more than doubling the time before the cancer began to progress compared with a placebo.

Even when the tumors resumed growth, they did so more slowly, delaying the time until a new treatment was needed. Results were so impressive that the study was “unblinded” early so that people on a placebo had the opportunity to switch to vorasidenib.

New Experimental Drug Shows Promise for Brain Cancer

Vorasidenib Blocks IDH1 and IDH2 Enzymes by Crossing Blood-Brain Barrier

Mutations in two specific genes — called IDH1 and IDH2 — cause tumor cells to produce abnormally high amounts of enzymes that drive cancer growth. Vorasidenib, made by Servier Pharmaceuticals and taken as a pill once a day, blocks both IDH1 and IDH2 mutant enzymes.

The drug works because its chemical design enables it to cross the blood-brain barrier, a network of blood vessels and tissue with closely spaced cells. Developing drugs that can travel through this tight seal has proved to be a major challenge for treating brain tumors.

“Having a therapy that penetrates the blood-brain barrier and shuts down specific cancer enzymes represents an important potential advance in treating brain tumors,” Dr. Mellinghoff says. “We’ve been very fortunate at Memorial Sloan Kettering to play a leading part in this effort from the very beginning.”

Why a New Glioma Treatment Is So Important

While low-grade diffuse gliomas in adults initially tend to grow slowly, they are still associated with an unfavorable outcome, or poor prognosis. Symptoms of the disease include impaired thinking, blurred vision, numbness and weakness, and early death.

In addition, they usually occur in young adults, who face difficult choices about whether to get aggressive treatments after surgery — such as radiation or chemotherapy — or undergo an anxious period in which they “watch and wait” to see if the tumor is growing. Vorasidenib could offer a more effective treatment option that does not risk damage to cognition or motor skills.

Vorasidenib Slows Growth in Young Patient’s Low-Grade Glioma

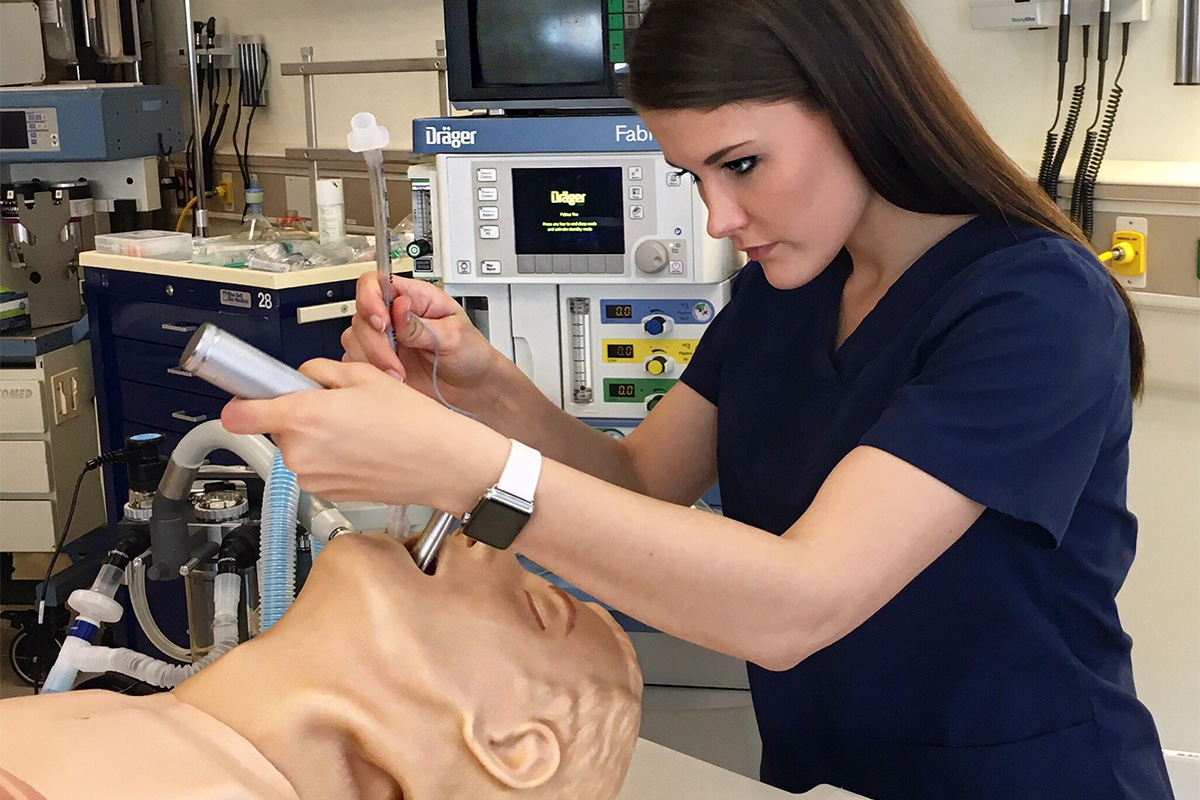

In late 2018, Alicia Kalogeropoulos, then 27, was enjoying the start of adult life. She had just gotten married, built her first house, and completed training to be a nurse anesthetist at a hospital in Lehigh, Pennsylvania. Trying to rest after a 16-hour shift, she heard her puppy, Porsche, causing chaos in the kitchen. Springing off the couch, Alicia tripped over the dog bed and hit her head on the floor. Fearing a concussion, she asked her husband, Alex, to take her to the emergency room for a CT scan.

The doctors told her there was no injury, but they had found something very troubling: a small mass. A follow-up MRI confirmed Alicia had a brain tumor.

“My husband called my parents to come hear the news in the ER and it was devastating for everyone,” Alicia says. “I didn’t believe it at first. You think of people with brain tumors having symptoms like headaches or problems thinking. But I felt completely normal.”

Alicia had surgery to take out the tumor in January 2019, in the same operating room where she provided anesthesia daily. Most of the tumor was removed except for a small part that could not be reached without risking damage to her ability to function normally.

“I was very scared because the only stories I’ve heard of people with brain tumors didn’t turn out well,” she says. “I never imagined such a large wrench would be thrown in all of our plans just a few months after reaching all those big milestones.”

Doctors at the hospital told her the tumor was almost guaranteed to grow again and recommended chemotherapy and radiation after the surgery. But Alicia worried about how these treatments could affect the rest of her life, including her fertility.

“I wanted to continue to work in my new career as a nurse anesthetist and needed all my faculties,” Alicia says. “I also wanted to feel as normal as possible, travel, hang out with friends, work out, and do things everyone else was doing.”

Alicia’s husband pushed for her to seek opinions from other doctors. She saw multiple specialists, all of whom told her to hold off on chemotherapy and radiation because of her age and the tumor being low-grade. But in late 2019, the tumor started to grow.

A doctor in Boston told her there was a lifetime maximum amount of radiation a person could receive to the brain and that she should save it for when the tumor started to become more aggressive. He suggested as an alternative that she consider the vorasidenib clinical trial at MSK. The multicenter trial, called INDIGO, was open to people with grade 2 gliomas that contained a mutation in IDH1 or IDH2 gene and whose only previous treatment was surgery.

Alicia came to MSK and immediately felt hopeful.

“Dr. Mellinghoff and the research nurses were excited and optimistic about vorasidenib,” Alicia says. “They made me feel like I was joining a team, not just a trial.” She decided to enroll in INDIGO and began treatment in April 2020.

Impressive Clinical Trial Results

In the INDIGO trial, 331 patients from 10 countries with a median age of 40 were randomly split into two groups. People in one group received vorasidenib once a day for four weeks. Those in the other group received a placebo over the same time frame.

The results were dramatic. In patients with grade 2 gliomas with IDH mutations, vorasidenib led to a 61% reduction in the risk of tumor progression or death and significantly delayed the need for more toxic therapy when compared with the placebo.

People in the vorasidenib group had a median progression-free survival — the length of time until the tumor started growing — that was more than twice as long as the placebo group (27.7 months versus 11.1 months). The median time until the next treatment was needed was also much longer in the vorasidenib group.

“We usually don’t see such striking results from a trial, where one drug makes such a difference in progression-free survival,” Dr. Mellinghoff says.

Less than 10% of patients had serious side effects from vorasidenib. The most common were liver enzyme elevations, which were reversible.

In Alicia’s case, the tumor unfortunately kept growing. By December 2021 — 20 months after she started the trial — the tumor was 20% larger. At that point, Alicia was allowed to be “unblinded” to find out which trial arm she was in. After learning she had been taking the placebo, she switched to vorasidenib.

“I was eager to be unblinded because I was in a Facebook group of trial participants, and the drug seemed to be working for many of them,” Alicia says. “I wanted to give the real drug a chance before moving on to the more intense therapies.”

After she started taking vorasidenib in December 2021, the tumor stopped growing. It has held steady over the past year and a half, causing no symptoms.

MSK’s Robust Brain Tumor Program

Dr. Mellinghoff explains that a critical step before moving vorasidenib toward a large phase 3 study was a phase 1 study, in which the drug was given to patients before their tumor was taken out. Examining the removed tissue confirmed that the drug crossed the blood-brain barrier and almost completely turned off the production of the critical metabolite in tumor cells. (The metabolite was a substance produced by the mutant IDH enzymes.) It also appeared to reverse molecular changes typically associated with active mutant IDH enzymes.

“The INDIGO trial has been a large international effort, but MSK has played a leadership role in testing this drug, starting with preclinical testing in my laboratory,” Dr. Mellinghoff says. “We’ve been very invested in brain tumor research, and we have many outstanding neuro-oncologists who can offer these trial opportunities to our patients throughout the New York City metropolitan area, as well as at MSK’s regional sites.”

Patients who would like to learn more about brain tumor treatment options at MSK should contact Patient Access Services at 800-525-2225.

Researchers at MSK and elsewhere are now conducting a phase 1 clinical trial investigating whether vorasidenib combined with the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab can be effective against grade 2 or 3 astrocytoma (a type of glioma) that contains an IDH1 mutation and has returned after previous treatments.

Living a Full Life

Today, Alicia leads a very active life, working 12-hour shifts, traveling with husband Alex — they especially love cruises — and hanging out at home with Porsche and their two other dogs, Tesla and Athena.

“I was very scared finding out I had brain cancer initially because I immediately thought this meant I was going to die,” Alicia says. “Over the past four-and-a-half years, I have learned to accept it as part of my life story. I am no longer scared because I have faith in the future of medicine and technology. Every day is another day closer to finding cures for all types of cancer.”

Alicia is especially grateful for her husband’s strong support — and toward Porsche, whose mischievousness inadvertently led to detecting the tumor she had more than four years ago.

“I call her my little angel,” Alicia says. “But she still misbehaves.”

This story was originally published in 2023 and has been updated.