Even as researchers design more-potent cancer therapies, they face a major challenge in making sure the drugs affect tumors specifically without also harming normal cells. This obstacle has thwarted many promising treatments.

Memorial Sloan Kettering molecular pharmacologist Daniel Heller and colleagues have devised a novel strategy for addressing this problem. Rather than aiming directly at cancer cells, they are focusing on targeting a molecule in the blood vessels that feed tumors and using nanotechnology to deliver tiny particles that will stick to the target and unleash their payload of cancer drugs.

The target, a protein called P-selectin, serves as a kind of molecular Velcro for cancer treatments. It is especially prevalent in blood vessels that nourish cancer itself — including metastatic tumors, which cause roughly 90 percent of cancer deaths and are especially hard to treat.

“The ability to target drugs to metastatic tumors would greatly improve their effectiveness and be a major advance for cancer treatments,” says research fellow Yosi Shamay, lead author of a new study describing this method that is featured on the cover of the June 29 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

P-selectin: An Inviting Target for Nanoparticles

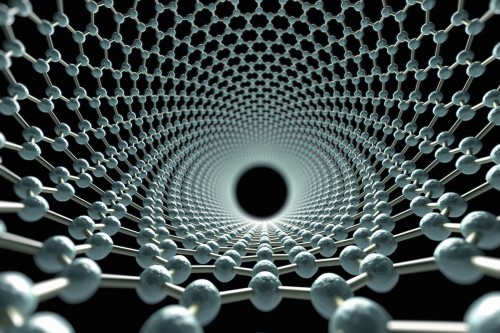

Dr. Heller’s laboratory investigates the use of nanoparticles — tiny objects with diameters one thousandth that of a human hair — to carry drugs to tumors. The drugs are encapsulated within the nanoparticles, which must home in on a target within or near tumors to deliver the therapies effectively.

P-selectin emerged as an especially good target for cancer-focused nanoparticles because in addition to being found in tumor blood vessels, the molecule aids in the formation of metastases. When cancer cells leave a primary tumor and circulate in the blood, the cells can adhere to P-selectin, exit the blood vessel, and form a new tumor.

“We know that cancer cells can come into contact with P-selectin to begin the formation of metastatic tumors,” Dr. Heller says. “So in effect, we’re hacking into the metastatic process in order to intercept the cells and destroy the cancer with drug-loaded nanoparticles.”

Exploring the Promise of Nanomedicine

Dr. Shamay made the nanoparticles out of a very abundant and cheap substance called fucoidan, which is extracted from brown algae that grows in the ocean. Fucoidan has a natural affinity for P-selectin, so the nanoparticle is simple to make and adapt.

“It’s difficult to develop a nanoparticle-based treatment that is effective and safe in lots of people,” Dr. Heller says. “You usually have to load both the drug and another component to the nanoparticle to enable the nanoparticle to bind to the correct spot — and any new element carries the potential to be toxic. But in this case, the nanoparticle itself is made of material that naturally attaches to the target.”

“Just by targeting the tumor blood vessels, we found that the drug is going to the tumor itself and killing cancer cells directly,” Dr. Heller says. “This makes the drugs delivered through this process work even better than we expected.”

Even when the tumor blood vessels don’t express P-selectin, the researchers could use radiation to trigger the expression of that protein in the tumor area before administering the nanoparticles. In collaboration with MSK radiation biologist Adriana Haimovitz-Friedman, they found that radiotherapy ensured that enough P-selectin was expressed for the nanoparticles to adhere to and deliver the therapy to the tumor.

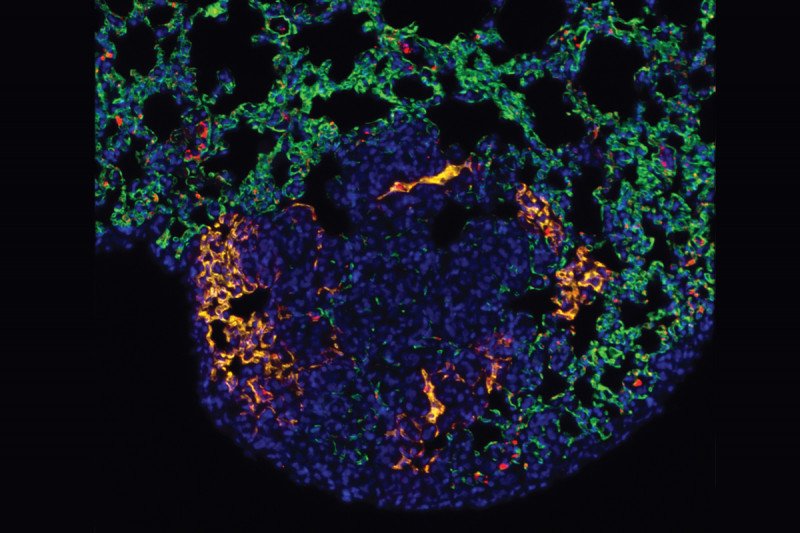

The researchers conducted experiments showing that the nanoparticles selectively attached to cancer sites, including metastatic tumors, in the lungs of mice. The nanoparticles were filled with different cancer drugs, including chemotherapies and newer precision medicines that target specific molecules in cancer cells.

“We demonstrated that the drugs were more effective when administered within the nanoparticles than when given alone,” Dr. Heller says. “We were able to give lower doses, which reduced the side effects.”

In collaboration with the laboratory of MSK Physician-in-Chief José Baselga and cancer biologist Maurizio Scaltriti, Dr. Heller’s lab used the nanoparticles to deliver a type of targeted therapy known as a MEK inhibitor, which has shown promise in several cancers. With this method, the MEK inhibitors were more effective against the tumors without causing the serious side effects, such as skin rashes, that have hampered many treatments.

“The clinical potential of nanomedicines for cancer has not been fulfilled, but targeting P-selectin with these nanoparticles is an approach that seems to be broadly useful for all kinds of drugs,” Dr. Heller says.

“This approach requires further in-depth testing, including clinical trials, but we are really excited about its promise.”