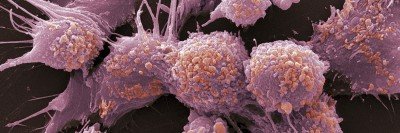

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men in the U.S., especially for those over age 50. Most prostate cancers are not a problem because they grow slowly. Many men get prostate cancer if they live a long life, but they die with prostate cancer, not from it.

The prostate is a small gland between the bladder and the base of the penis. This location means that diseases of the prostate (both cancer and non-cancer) can affect bladder and sexual functions. Nerves and blood vessels that control erectile function (getting hard) are near the prostate. They can be affected by prostate cancer or treatment for prostate cancer.

More than 9 out of 10 cases of prostate cancers are found when cancer is only in the prostate gland. When prostate cancer spreads, it can go outside the prostate capsule, a thick covering of the prostate. It can spread up into the seminal vesicles, 2 small tubelike glands on top of the prostate. Sometimes, prostate cancer can spread into lymph nodes in the pelvis, or into bones.

Treatment Options for Prostate Cancer

For people with slow-growing prostate cancer, we offer active surveillance. Some prostate cancers grow so slowly they usually will not cause problems. Your doctors will regularly monitor the slow-growing tumor for any sign it is changing.

Some people are interested in surgery, or it’s recommended by their doctor. Our surgeons are among the world’s most experienced in performing prostate operations. We’re always working to improve their safety and effectiveness. Radical prostatectomy is surgery to remove the prostate gland. We offer robotic as well as laparoscopic and open surgery. Our surgeons are also highly experienced in a procedure called salvage radical prostatectomy. It is sometimes an option when prostate cancer returns after treatment with radiation therapy.

Radiation therapy (radiotherapy) uses high-energy beams to treat cancer. It works by damaging the cancer cells and making it hard for them to reproduce and spread.

Our radiation oncology team is one of the most experienced in the world in treating prostate cancer with many types of radiotherapy. Our oncologists (cancer doctors) have broad experience with:

- Image-guided, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IG-IMRT)

- Stereotactic high-precision radiosurgery (similar to CyberKnife)

- Stereotactic hypofractionated radiation therapy (MSK PreciseTM)

- Low-dose-rate permanent seed implants (a type of brachytherapy)

- High-dose-rate temporary seed implants (a type of brachytherapy)

Our doctors pioneered and continue to improve these therapies. We have experience in all types of radiation therapy and can offer a treatment that’s best for you. We also developed and improved complex tools to target very precise, powerful doses of radiation directly to a tumor. These tools include advanced linear accelerators, imaging approaches, and high-speed computer-based systems.

Small, localized (only in the prostate) tumors: Treatment includes focal therapy, or partial gland ablation. Focal therapy is a general term for some treatments that are not invasive (nothing is put inside the body). They use freezing, heat, or electricity. Another approach is highly targeted seed implants that destroy only the portion of the prostate that has cancer. This is very helpful for people who already had radiation therapy, but cancer returned to the prostate itself. Our brachytherapy experts are very experienced in these complex procedures.

Aggressive cancers: There’s risk of it spreading into tissues next to the prostate, or to lymph nodes. In such cases, we combine treatments such as hormone therapy, brachytherapy, and external beam radiation therapy.

We treat the areas that are at risk so there is less radiation exposure for normal healthy tissue. This approach lets us give high radiation doses to the prostate and lower doses to nearby tissue. It gives you the best chance of a cure and lowers the long-term side effects of treatment.

Prostate cancer clinical trials: MSK patients have access to research studies, also known as clinical trials, that investigate new and better treatments for prostate cancer. Sometimes these studies offer therapies years before they’re available anywhere else.

Rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level after a radical prostatectomy: One possible cure is external beam radiation therapy, with or without hormone therapy. Hormone therapy can shrink and slow the growth of prostate tumors, even after the cancer has spread. During external beam radiation, a treatment machine aims beams of radiation directly to the tumor. Our radiation oncologists use highly targeted IG-IMRT. Patients get the lowest risk of long-term side effects from radiation therapy.

Prostate cancer that has spread outside the prostate: These are treated with several systemic therapies. They include:

- Hormonal therapies

- Chemotherapy

- Genomic-based treatments (based on genetic information)

- Immunotherapy

- Radiotherapeutics (radioactive medications)

- Biologics

- Clinical trials

Our medical oncologist experts will decide which treatments are best for you and the kind of prostate cancer you have.

Advanced prostate cancer: MSK offers clinical trials that test targeted therapies and new approaches to treatment. Our research studies have changed how advanced prostate cancer is treated, using such drugs as abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, and rucaparib. We are leaders in developing new diagnostic imaging and genetic studies that help match a specific cancer with the best treatment. We are also the coordinating center for the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium. This collaboration among 13 leading centers focuses on early drug development and clinical trial design.

Oligometastatic prostate cancer: In some cases, we can offer treatment for prostate cancer that has metastasized (spread) to a few areas in the bones. Stereotactic radiosurgery can treat both the prostate and the sites of metastatic disease. It may be combined with other treatments, such as surgery or systemic therapy, to improve outcomes.

Follow-Up Care

Many people treated for prostate cancer have serious side effects. Our follow-up care experts offer programs to help you cope with or overcome those problems. Our goal is to help you maintain a good quality of life. MSK’s Male Sexual and Reproductive Medicine Program serves people who have changes in their sexual and reproductive health. In addition, our comprehensive Adult Survivorship Program can help you adjust during and after cancer treatment. Watch a video to learn more about MSK’s Adult Survivorship Program.