Common Names

- Magic mushrooms

- Shrooms

- Boomers

- Buttons

- Purple passion

- Mushies (>12 other terms)

For Patients & Caregivers

Tell your healthcare providers about any dietary supplements you’re taking, such as herbs, vitamins, minerals, and natural or home remedies. This will help them manage your care and keep you safe.

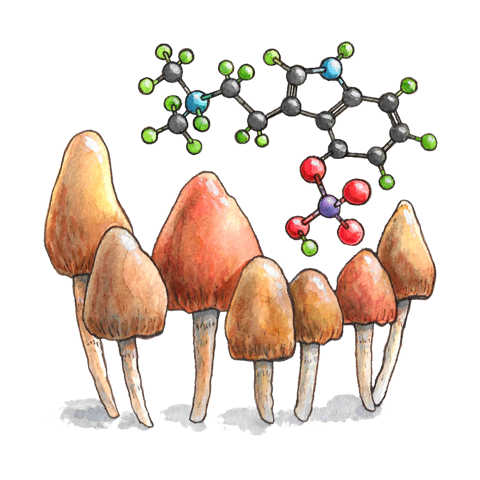

Psilocybin is a substance found in more than 200 species of fungi commonly known as magic mushrooms.

Psilocybin mushrooms are eaten for their hallucinogenic effects. They are also brewed as teas or added to other foods to mask their bitter taste.

Psilocybin is used to:

- Treat tobacco addiction

- Treat alcohol addiction

- Treat depression

- Reduce anxiety (strong feelings of worry or fear)

- Treat obsessive compulsive disorder

- Treat migraines

- Improve mood

- Improve cognition (the mental action of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought)

Psilocybin also has other uses that haven’t been studied by doctors to see if they work.

Talk with your healthcare providers before taking psilocybin. It can interact with some medications and affect how they work. For more information, read the “What else do I need to know?” section below.

- Headache that lasts for a short time a day after the treatment

- Increased blood pressure

- Increased heart rate

- Anxiety (strong feelings of worry or fear)

- Confusion

- Fatigue (feeling more tired than usual)

- Nausea (feeling like you’re going to throw up)

- Vomiting (throwing up)

- Dizziness

- Suicidal ideation or behavior (thinking about or planning suicide), or self-injury

Don’t take psilocybin if:

- You have a history of schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Psilocybin may make these conditions worse.

- You have serious or uncontrolled heart conditions. Psilocybin can make these conditions worse.

- You’re pregnant or breastfeeding. Psilocybin may not be safe for you.

- You’re taking antidepressant or antipsychotic medications. They can increase the effects of psilocybin.

- You’re taking medications that increase serotonin, a chemical made by some nerve cells. These include drugs that lower your appetite and reduce anxiety. When taken with psilocybin, they can increase serotonin in your body. Higher levels of serotonin can cause reactions that include increased heart rate, sweating, seizures and muscle breakdown.

For Healthcare Professionals

Psilocybin is an indole alkaloid found in more than 200 species of fungi commonly referred to as “magic mushrooms,” many of which belong to the genus Psilocybe. Historically used for religious ceremonies and healing rituals by Mesoamerican cultures, psilocybin mushrooms are ingested orally for their hallucinogenic effects. They are also brewed as teas or added to other foods to mask their bitter taste. Upon consumption, psilocybin is converted to psilocin, which has psychoactive properties.

Psilocybin is a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act, but renewed interest in its therapeutic potential for treating mental health issues has led to a surge in clinical research in recent years. Randomized controlled trials have reported benefits of psilocybin-assisted therapy for

- Tobacco use disorder (1)

- Alcohol use disorder (2)

- Treatment-resistant depression (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (47)

- Major depressive disorder (48)

Systematic reviews/meta-analyses showed

- Improvements in end-of-life anxiety (9)

- Positive effects on existential and spiritual well-being, quality of life and acceptance in patients with terminal illness (10)

- Effectiveness comparable to escitalopram for long-standing depression (11)

Preliminary findings also suggest beneficial effects in individuals with

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (12)

- Cluster headaches (13) (14) (49)

- Migraines (15)

- Demoralization with an AIDS diagnosis (16)

In cancer patients with psychological distress, psilocybin affected

- Reductions in suicidal ideation (17)

-

Rapid, significant, and sustained reductions in depression and anxiety (18) (19) (20)

Notably, mystical experience – characterized by deep feelings of meaning/sacredness, interconnectedness, transcendence of time and space, and a strong positive mood – was positively correlated with reductions in depression (18). - Integrated group and individual psilocybin-assisted therapy may improve patients’ experience (50).

Microdosing: Consuming very low doses of psychedelics for improving mood, concentration, creativity, and cognitive function is also gaining popularity. Studies are mixed on whether microdosing can improve mood and mental health (21) (22) (23) (24). A case series suggests it may relieve chronic neuropathic pain (25).

Legal Status: Under federal law, the use, sale and possession of psilocybin is illegal. Given the promising preliminary data, the USFDA granted “breakthrough therapy” status to psilocybin in 2018 for treatment-resistant depression, and in 2019 for major depressive disorder. This designation can help minimize the burden of federal regulations that impede research and drug development. Many states are also moving toward decriminalizing psilocybin for therapeutic or recreational purposes: Oregon became the first to both decriminalize and legalize psilocybin for therapeutic use, with ballot initiatives underway in Colorado and California (26).

The American Psychiatric Association supports research into psychedelics, but states that “clinical treatments should be determined by scientific evidence in accordance with applicable regulatory standards and not by ballot initiatives or popular opinion” (46).

In Summary, emerging evidence suggests that psilocybin improves mental health outcomes in patients with multiple psychiatric conditions. With increasing public interest and acceptance of psychedelic therapies, larger trials with more diverse populations, standardized dosages, stronger blinding/controls, research on long-term effects, as well as clear regulations and guidelines are needed to inform future clinical practice (27).

It is important to note that although psilocybin has low potential of addiction (28) and is associated with lower risk of adverse effects compared to other psychoactive drugs such as LSD or MDMA, it can cause acute psychological distress, dangerous behavior and sustained psychological discomfort in uncontrolled environments (29). Individuals who abuse psilocybin mushrooms may also risk poisoning because their morphological similarities to some poisonous mushrooms could lead to misidentification.

- Tobacco use disorder

- Alcohol use disorder

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Obsessive compulsive disorder

- Migraines

- Mood

- Cognition

Psilocin, the active metabolite of psilocybin, is known to produce perceptual changes, altering one’s awareness of surroundings, thoughts, and feelings. These effects are exerted primarily via serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) type 2A receptor agonism (30). This functional selectivity to the 5-HT2A receptor leads to releasing increased levels of glutamate, which may also contribute to the psychedelic effects. The visual hallucinations associated with psilocin are likely due to overexpression of 5-HT2A receptors in the visual cortex (31).

Additionally, psilocybin is thought to decrease negative affect and the neural correlates of negative affect, thought to be one of the mechanisms underlying its effects against a variety of mental disorders (32).

Following oral consumption, the bioavailability of psilocin was reported to be approximately 50%, with detectable levels in the plasma after 30 min (33). Recent studies using a 25 mg dose of psilocybin found the onset of action at 20-40 minutes with effects peaking at 60-90 minutes, and active duration between 4-6 hours (34). The Tmax (maximal plasma concentration) was 18.7 ng/ml - 20 ng/ml at 120 minutes (35) (36). Nearly 80% of the circulating psilocin is metabolized by hepatic phase II glucuronidation (conjugation) through UGT 1A10 and UGT 1A9 enzymes. Psilocin is completely excreted within 24 h with much of it occurring within the first 8 h (33) (37).

- Those with a personal or family history of schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder should avoid psilocybin (18) (6) (3) (4) (5).

- Those with serious or uncontrolled cardiovascular conditions should avoid psilocybin (6).

- Pregnant and breastfeeding women should also avoid it given the insufficient evidence to assess risks.

Clinical studies have reported transient headache the day following the treatment, increase in blood pressure and heart rate, anxiety, confusion, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, dizziness and suicidal ideation or behavior or self-injury. (3) (20) (5) (8) (2) (12) (6) (28) (38) (51)

Case Reports: Psilocybin use has also been associated with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (39), rhabdomyolysis (40), prolonged mania, psychosis and severe depression (41), unpredictable behavior (42), toxic metabolic encephalopathy (52), manic episodes (43) (53), seizures (54), cardiac arrest (55) and persistent pupillary changes (44).

- Antidepressants/Antipsychotics: Concurrent use may result in heightened or blunted psychedelic experience (33).

- Serotonergic drugs: Simultaneous use may cause serotonin syndrome in which excessive serotonin signaling may potentially lead to life-threatening adverse reaction (28).

- UGT substrates: Psilocin is metabolized by UGT 1A10 and 1A, and therefore, concurrent use of medications that inhibit or induce UGT enzymes should be avoided (37) (45).